OPINION

Lives at stake

Youths guilty of mindless random violence must expect to see consequences

All of a sudden, rival gangs of suburban teenagers were no longer just playing at being tough guys. The constant bullying and dire threats of a group of try-hard gangstas had become very real. Teenager Steven John Rowe lay dying on a pitch-black Woodvale pathway on Halloween night 2008, felled with a blow to his head from a wooden stake as rival groups played out an ultimately fatal game of tit-for-tat retribution.

The 17-year-old boy who snuffed out his young life was only the second person charged under this State’s one-punch homicide law passed three months before.

He appeared before one of our most experienced jurists, Eric Heenan, the fifth-ranking of more than 20 Supreme Court judges.

Justice Heenan was appointed to the bench in 2002 after more than 30 years as a lawyer, 16 of them as Queen’s Counsel.

Anyone who reads his introductory sentencing remarks published on this page today can’t help but be struck by his heavy heart at the events leading up to Steven’s fatal blow. Justice Heenan was telling the community that everyone had to take responsibility for the development of a youth culture which caused a chain of events that spun rapidly out of control.

It’s the lesson parents desperately try to drum into their children: actions have consequences.

According to Justice Heenan, had the blow been struck three months earlier, it would not have been an unlawful homicide in any form.

The very fact that the jury threw out the original charges of murder and manslaughter meant they accepted there was an element of accident to the death, which might have seen the offender walk free under the old law.

But Justice Heenan notes that the conviction on the one-punch charge of unlawful assault causing death “resulted because the jury was satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the requirements of lawful justification or excuse for self-defence had been disproved”.

Even though the accused juvenile, known only as JWRL, could plead self-defence because of the very real threat to his safety, the jury found he simply hit Steven too hard.

He was sentenced to two years jail, suspended for two years.

Two weeks ago, the Court of Appeal handed down its verdict on the Director of Public Prosecutions’ objections on four grounds, asserting the sentence was manifestly inadequate, that Justice Heenan made two errors in law and, most importantly, was wrong in assessing JWRL’s culpability. In rejecting all grounds, Chief Justice Wayne Martin went a long way to clarifying how the new one punch law will operate and how the defence of self-defence will impact on it.

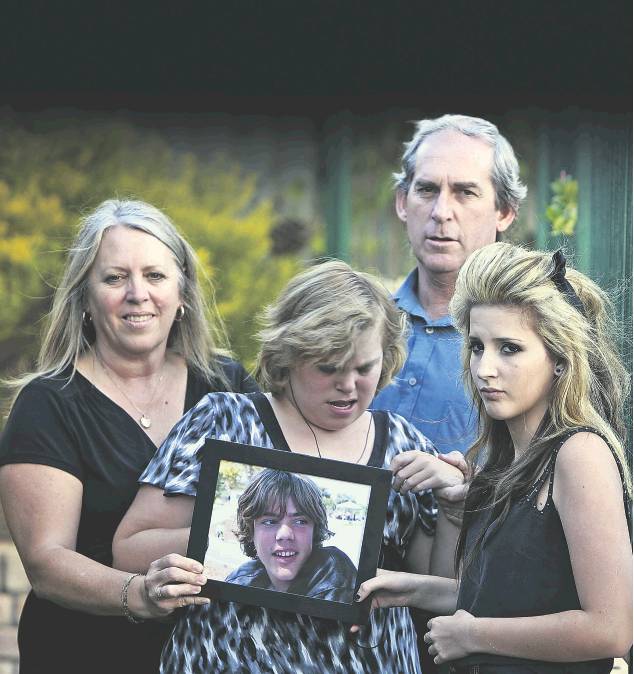

Picture: Lee Griffith

As I reported in a column on Tuesday, central to the issue of self-defence was evidence of threats made by one of the main players, RC, which was not disclosed by the DPP prosecutor, earning a rebuke from Chief Justice Martin.

It was admitted in the appeal court hearing, significantly bolstering the three judges’ support for Justice Heenan’s decision.

What effect it would have had on the original trial will never be known.

A lot of people associated with this case, including the Rowe family, dispute some of the evidence on which Justice Heenan made his findings, especially how Steven and RC, a boy notorious for his violent nature, confronted JWRL and a mate on the pathway. That’s beyond the scope of this article.

But a key part of the appeal judgment deals with the reasons JWRL armed himself with the stake he found beside a pathway after walking his girlfriend home, avoiding on both legs of that trip milling gangs of drunken teenagers.

Simply put, Justice Heenan found he was frightened of Woodvale’s gang culture. Many people in the suburb seem to be in denial that it exists, despite the trial’s evidence.

“The picture painted for the prosecution in the course of the trial was that JWRL was carrying this ‘weapon’ without any justification and by so doing exhibited an inclination and a preparedness to use violence,” Justice Heenan said.

The prosecutor drew the inference that JWRL “was intent upon, or ready to use, such force as would be likely to cause serious bodily injury”.

“That approach must be regarded to have been rejected by the jury and I also reject it,” Justice Heenan said.

And it’s here that Chief Justice Martin’s decision on the apparently light sentence is important.

“Given that JWRL caused Mr Rowe’s death by striking him on the head with a piece of wood using considerable force, a sentence of imprisonment was appropriate,” Chief Justice Martin found.

“However, as the culpability of JWRL essentially lies in the use of excessive force in a situation in which the use of lesser force would have been justified, that period is appropriately placed at the lower end of the range, given the age and antecedents of JWRL.”

In a very pointed comment, Justice Heenan noted that the new law had come about without reference to the Law Reform Commission, darkly hinting at populism.

“It is reasonable to infer from the elements of the offence that it was created by the Parliament in response to rising concerns in respect of levels of violence in the community, and the consequences of violence, whether foreseen or unforeseen,” Chief Justice Martin said.

“Violence always carries with it the risk of serious unforeseen consequences, as this case tragically demonstrates.”

The Rowe family remains bitter that justice was not done for their dead son. But what the two judgments in this case have shown is that there may be little protection from the courts when gangs of young people take part in mindless, random acts of retaliatory violence, despite the intent of the new law. If suburban gangs are going to act in that way, they are on notice they have to expect the consequences.

Violence always carries with it the risk of serious unforeseen consequence.

CHIEF JUSTICE WAYNE MARTIN