Troubled teens find direction

PILOT PROGRAM

Joseph Catanzaro

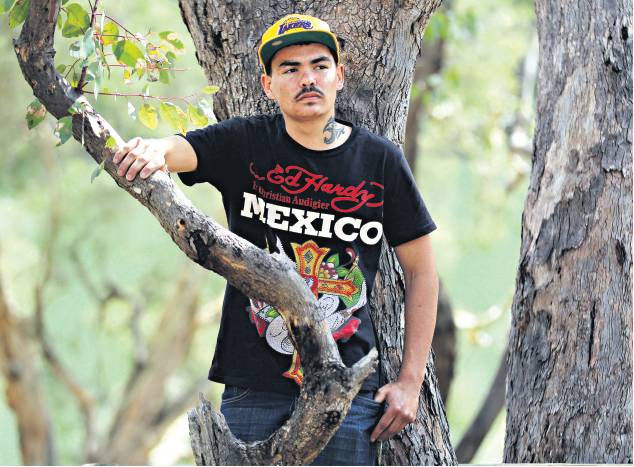

Zack Dean’s mates had stolen a car. They wanted him to go for a ride. It was nothing the 19-year-old Midland resident hadn’t done before.

“Stealing cars and breaking into houses is what we used to do, every day,” Mr Dean said.

He’d had brushes with the law. He’d scrapped and boozed and been around the block enough times to realise a big choice when it confronted him.

Mr Dean told his friends he wasn’t getting into that stolen car.

The next day they were arrested after a dramatic highway pursuit.

“I could have been in that car,” Mr Dean said. “They all ended up in jail. I look at it now and think I could have been there with them.”

But he wasn’t, because with support from a groundbreaking new program aimed at helping troubled indigenous youth, Mr Dean is one of an increasing number of young men getting their life back on track.

On September 28, 2010, 16-yearold Swan View resident Jamie Collard was burnt to death after becoming trapped in a car his friend torched outside Bassendean shopping village. The incident made headlines. But what went largely under the radar was the trauma that radiated through the tightknit, local indigenous community.

Sam Mesiti, youth manager of crime prevention group Outcare, said the tragedy caused many troubled and frustrated youths to fall off the rails. With funding from the Department of Sport and Recreation and the Office of Crime Prevention, he developed the Live Works pilot program.

Mr Mesiti said programs that offered one day a week of counselling and interaction were not effective in helping disadvantaged youths. Live Works took a different approach.

“We started off with a program that was 20 weeks, five days a week,” Mr Mesiti said. The results were promising.

He put the youths to work renovating State housing properties. They worked five days a week, learnt basic trade skills and helped the local community in the process.

At the same time, counsellors would identify other areas where the young men needed help. Mr Mesiti said about 85 per cent of children in juvenile detention were indigenous and the recidivism rate was about 70-80 per cent.

Live Works, which puts 40 youths through the program a year, costs about $500,000 annually— the price of keeping two youths in detention for 12 months.

Of the roughly 60 youths who have come through Live Works, about 35 per cent have found work. Mr Dean said he was excited about the future.

Last week, at a camp in Bickley where new and old program participants spent five days learning about their culture and exploring a sense of self-worth, Mr Dean got another phone call.

“I’ve just got an apprenticeship with Dale Alcock Homes doing roof carpentry,” he said. “I’m excited to start working and earn my own money to buy a car, and to move on to a house.”